The Construction of Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B

A very personal and technical written and photographic history, by James MacLaren.

Page 68: Intertank Access Arm Lift plus How The FSS Came To Be, and More Hydrogen Than You Can Stand,

with Maybe Just a Little Bit of Art, Aesthetics, and Ballsy Ironworking Down near the Bottom.

| Pad B Stories - Table of Contents |

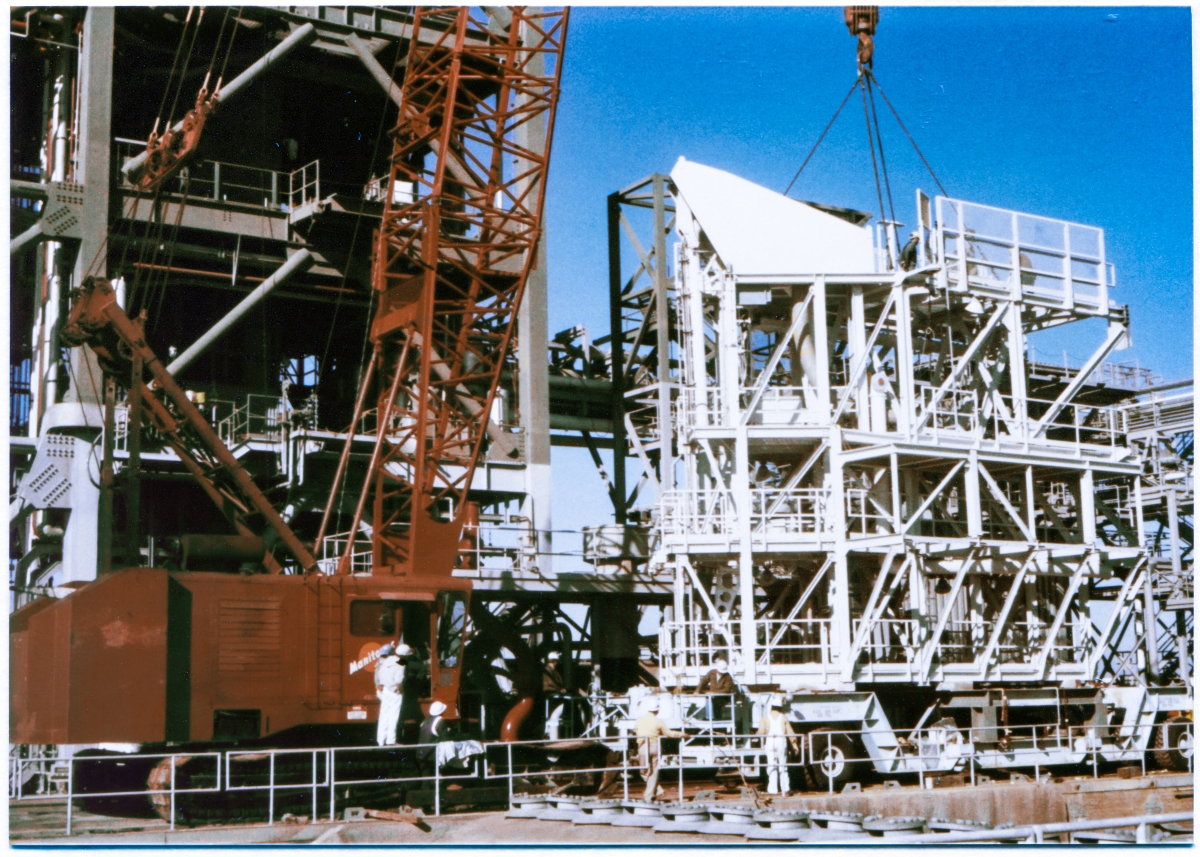

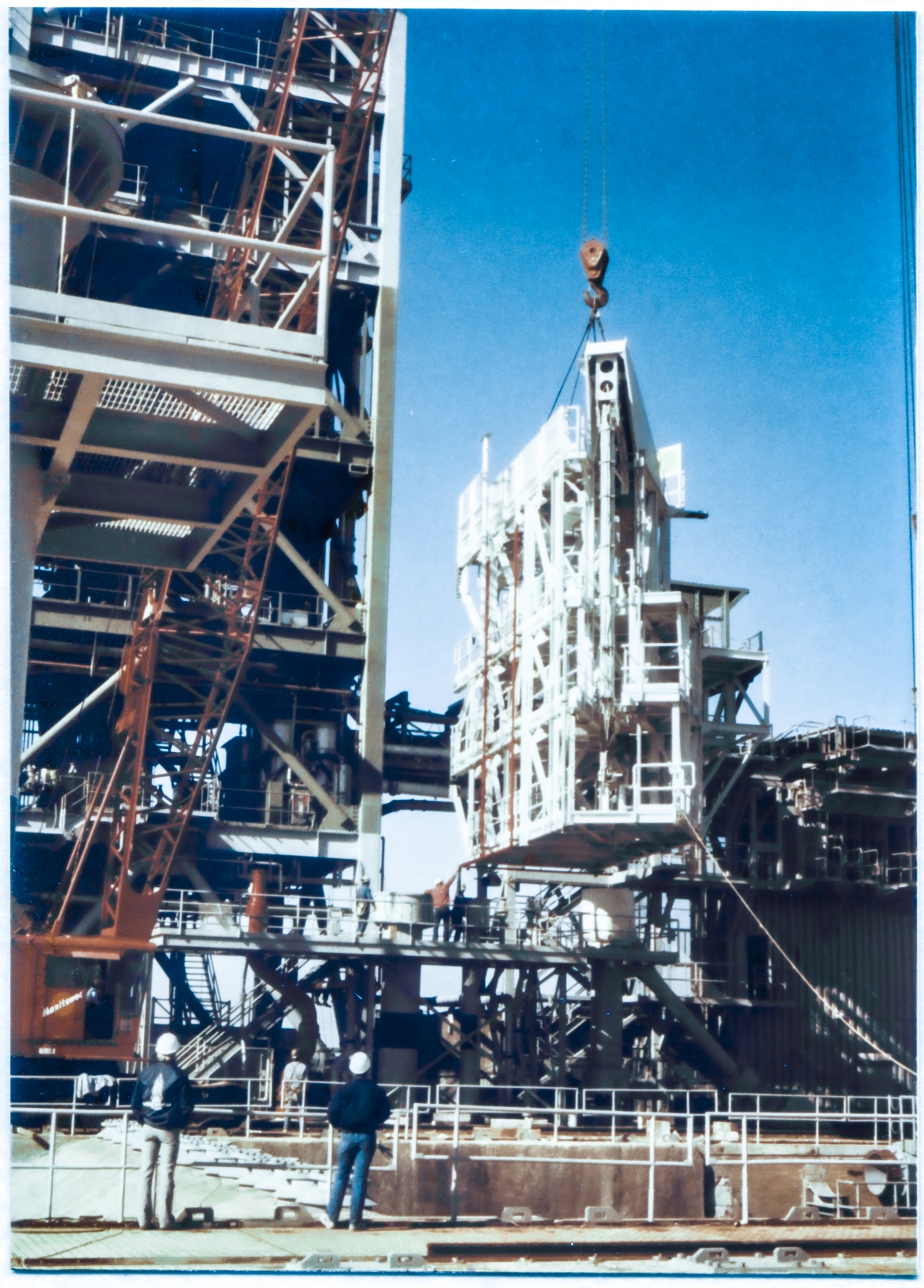

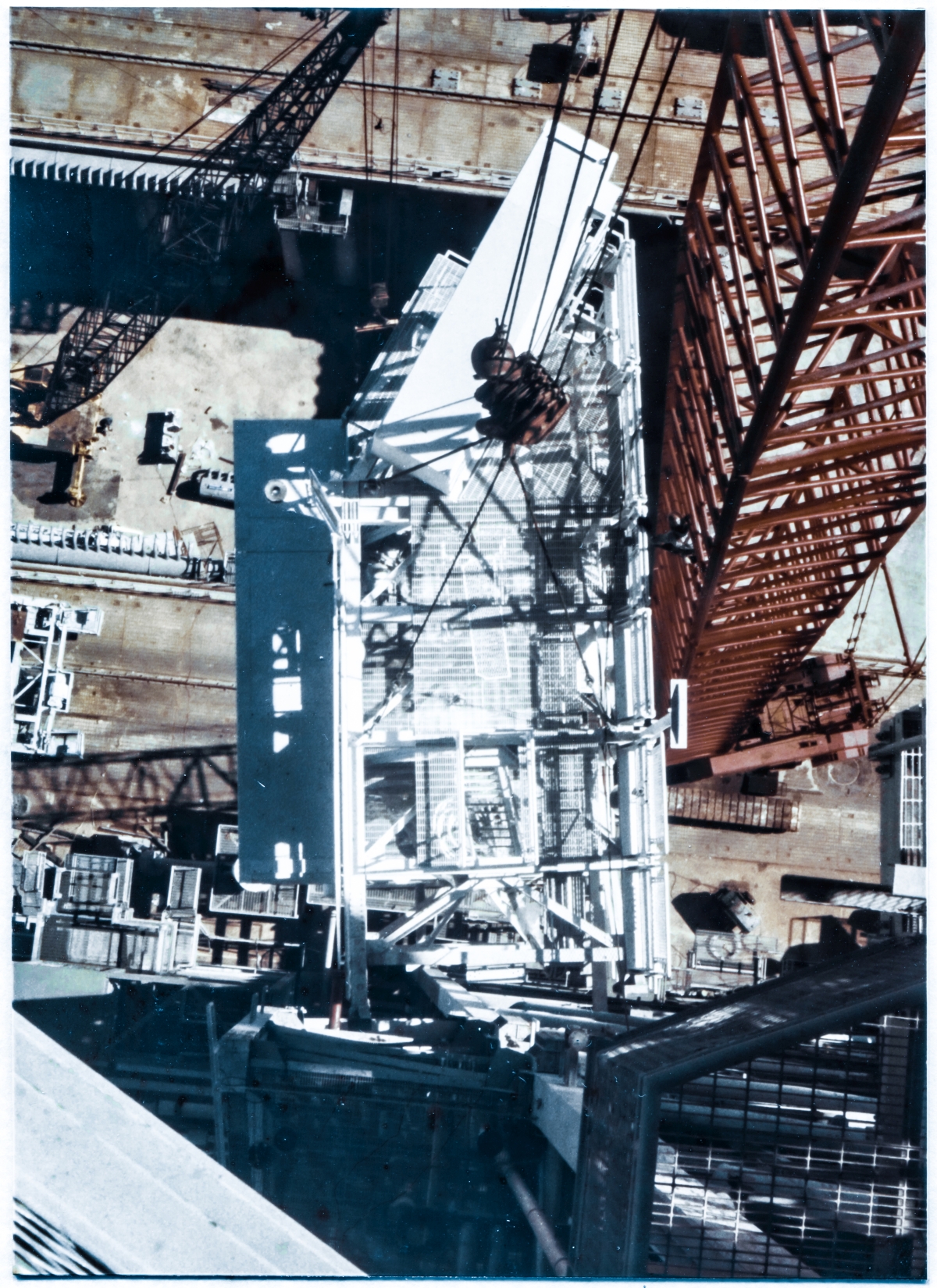

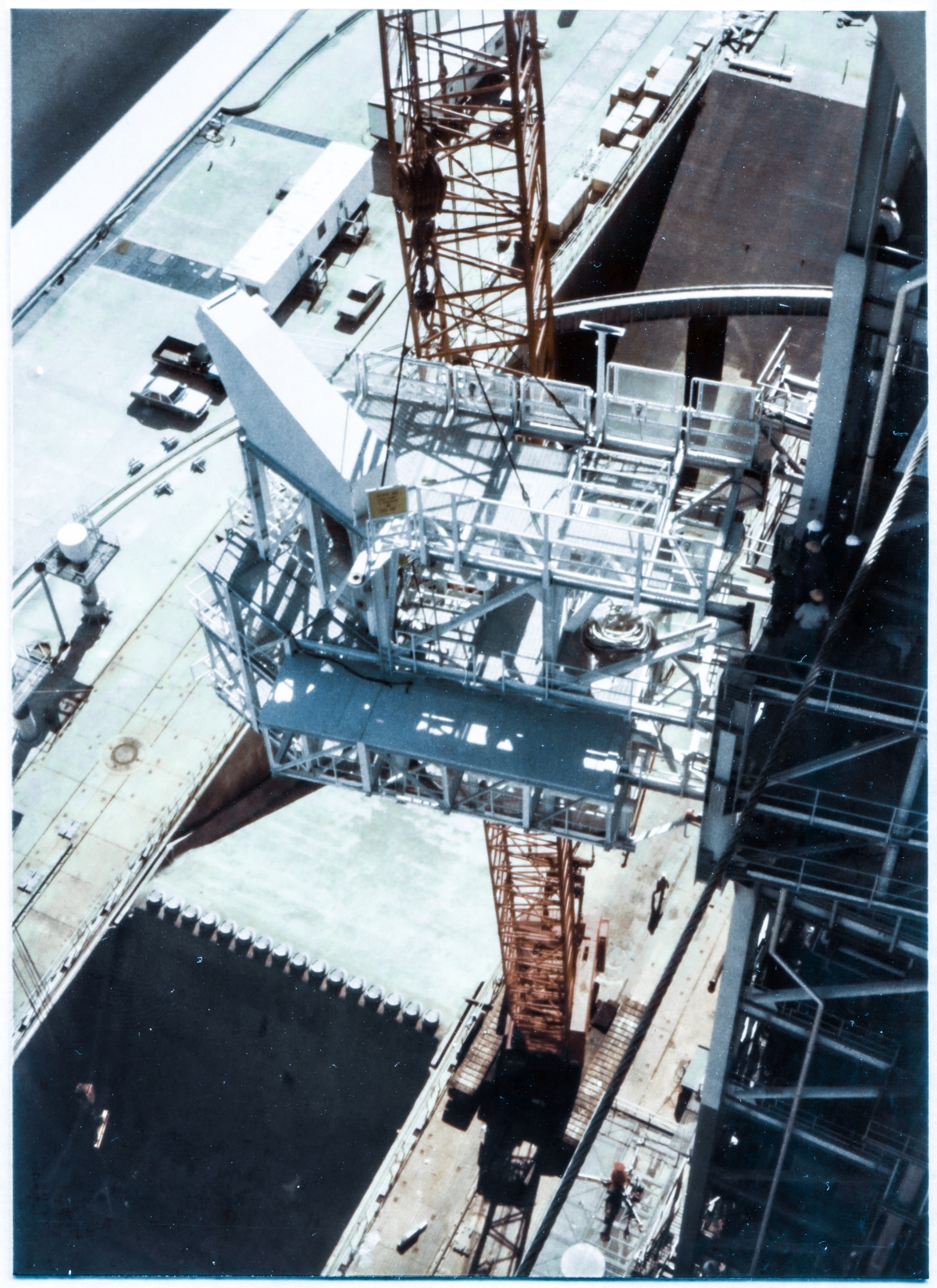

We have already lifted the OMS Pods Heated Purge Covers, the GOX Arm Strongback, the OMBUU, and the GOX Arm and its Vent Hood. We are now deeply into that part of the contract where we were continuing to lift various large and complex pieces of GFE (Government Furnished Equipment) and hang them on the towers, and today we're going to lift the heaviest piece of all, the External Tank Gaseous Hydrogen Vent Arm, which was also known as the Intertank Access Arm, and which was invariably referred to out on the Pad strictly by its acronym, the IAA.

And, weirdly enough, the actual Arm part of this monstrosity (which is the part that hangs on hinges and actually swings as all good "swing arms" do), was not included in the Lift this day. That Swing Arm is attached directly to this thing, and when it's folded back out of the way, not being used, it lives over a kind of "balcony" or maybe a sort of a "porch" or something, and that part of things sticks out away from the main body of this beast, running along its length midway between its top and bottom, and you can see it in our photograph, but of course, structural steel works hard to hide things, even when we're looking directly at them in plain sight... but it's there, and you can see it. But the Swing Arm itself isn't there, and it didn't show up until a fair bit later on.

The Swing Arm part of things was much smaller than the ridiculously way-too-big contraption you see in the image above (and for the love of god, I've lived in goddamned apartment buildings that were smaller than this particular drug-induced hallucination), and I never got a chance to photograph them lifting that part of the IAA system, and bolting it on to this thing, because the work at Pad 41, more and more, and more, was taking me away from activities on Pad B, and there was much that I missed as a result.

And before we can understand the Lift, we need to understand the thing that was getting lifted, and to understand what's getting lifted in our photograph above these words, we're going to have to back away from it, and use a pair of isometric views of it, to kind of see what's going on in the photograph.

First, we'll look at an isometric view, which shows us the whole thing, fully-assembled, hanging off the northeast corner of the FSS, protruding outward an alarming distance toward the Space Shuttle, of which all they're showing us is a section of the External Tank, but it does so in a less-than-fully-helpful way.

So here's 79K24048 sheet M-335, plain, without any colors or labels to help you understand what you're seeing. All that's been done to this image is the rectification, which seeks to straighten out (as much as possible, which is a very limited thing) the lines by removing the distortions which come with the original image I'm forced to work with. And when you look at the drawing border, you can immediately see that in order to render the contents of the drawing as straight and true as possible, the border went to hell and wound up unstraight and untrue, but such is life. But that's all that's been done to it. Nothing else. Plain vanilla all the way, baby.

But that's not very satisfying, and it doesn't really give you a proper feel for where we really are in any kind of accurate way, and we're gonna mark it up some, to give you a somewhat better feel for exactly where you are, and exactly what you're looking at, using that same drawing, M-335, to do it.

So here's 79K24048 sheet M-335 colored and labeled to let you see the main players, RSS, FSS, IAA, and ET, with each one labeled.

I'll leave it as an exercise to you the reader to find the little Lego Minifig looking guy that whoever was on the drafting board this day decided to include as perhaps a bit of reference for the scale of things, and then I'll further leave it as an exercise for you to consider how our little Minifig was actually rendered, vis-à-vis the handrail they appear to have their left hand resting upon the top runner of, which would appear to place that top runner near neck-level with them, and then remember that those top runners were OSHA mandated at 3'-6" to the top edge of the 1½"Ø schedule forty steel pipe, above the flooring they were guarding the edges of, and maybe take a guess at how tall, or perhaps short, our little Minifig person actually is. And in case you doubt me with the use of the top runner, the intermediate handrail runner is exactly waist level on our Minifig Guy, and those intermediate runners were also OSHA mandated, at 1'-8" on-center above the flooring they guarded.

These are hard numbers without margin or wiggle room for moving stuff around. They is what they is, and they ain't nothing more nor nothing less. Engineering drafting and the human form, for some odd reason, never seem to go together, and if somebody is good at one, they tend to be poor at the other, and our drawing packages reflect this sort of thing in too many places to enumerate, and... I've always wondered... why?

But even when M-335 is colored and labeled, it still doesn't match our photograph and to get to the bottom of that, we're going to have to return to a drawing I showed you on the previous page, sort of in passing, and once we've looked at that drawing, we might have to combine the two, into yet another Frankendrawing, as I've been forced into doing a few times previously, in this narrative.

And 79K24048 sheet M-336, which you've already encountered, when I drew your attention to this end of things on the previous page, is where we're going to take a large portion of Frankenstein's Monster, and graft it on to the rest of the creature, in the hope that it will allow you to better understand what the fuck it is that's really going on with our Lift.

And when you combine the two drawings together, and you get yourself a nice 79K24048 sheet M-335-336 Frankendrawing.

And with the Frankendrawing, the stupid Swing Arm is no longer there, getting in the way and confusing the issue, nor is any of the rest of the Hinge and Latchback apparatus, and now we stand a fighting chance of actually understanding what the fuck we're going to be looking at, in the coming series of photographs.

Yes, it contains clearly-visible inaccuracies and distortions, and I'm fully aware of that, and the time and effort required to completely eradicate that stuff when pasting the body of the beast onto its new background struck me as unreasonable, so I just kind of swiped at it, and decided "That's good enough," and moved on. Warts and all, it gets the job done, and that's all I care about, ok? It lets you see how this crap all fits together, as it existed on the day we Lifted the goddamned thing. And I didn't bother to clean it up elsewhere all too very much, either, and the Frankendrawing still has some original black-line labels to things that no longer exist on it, and I left those original black-line labels there, to let you know there's more to this thing, than meets the eye on the Frankendrawing. Feel free to go back to the unaltered version of M-335 if you'd like to continue admiring that stuff. Whatever. I don't give a shit.

Except, of course, that it's never going to be that easy, and you'll notice I took the time and trouble to highlight and label the IAA Support Structure on the FSS, and that was for a reason, and the reason is because it's what holds the whole nightmare schmutz up in the air, and maybe we'd best step back away from things yet again, and give this thing the attention it is so very much worthy of, because, hey, it's what they're gonna be bolting this motherfucker on to, once they get it up in the air, and...

It's kind of interesting on its own, anyway, and we're here, so...

...ok.

And waaay back on Page 14 is where you first were shown the Support Structure, but back then you were very young, and very new with this stuff, and I just sort of waved at it as we went by, and did not overburden you with it at the time.

But now...

...it's time.

So. To review, here's north side of the whole FSS (Side 4), viewed from an unusual location (I've never found so much as a single other image, taken by anybody, taken at any time, looking at it from this viewpoint) behind and beyond the 9099 Building on the concrete of the Pad Deck, kind of over by the LOX Tower, but out and away from it to the northwest, some.

And here's a reduced-scale version of that same image, Image 013, with the IAA Support Structure highlighted.

And back in the very beginning, before the FSS became an FSS and was instead a LUT, this area, extending down from the top of the tower one hundred feet on Side 4 of that LUT, was bare, and our IAA Support Structure did not exist.

We can look at Side 1 and Side 4 of the original LUT in 75M05121 sheet 1, which is the cover sheet for the whole works (despite the weird-ass fact that the structural drawings for the LUT carried a 75M number that was one digit lower), as designed and built by von Braun and Crew, and there is not the slightest hint of any kind of any thing where the IAA Support Structure appeared, nearly 20 years later.

Observe.

75M05120 sheet 46 for Sides 1 and 2 of the original LUT.

And 75M05120 sheet 47 for Sides 3 and 4 of the original LUT. And of course it's Side 4 where we will find our IAA Support Structure on the FSS at Pad B, although, when looking at either Side 1 or Side 3, it will also be visible, hanging off of the side of the tower.

So we return once again to the present part of the narrative, and we see on 79K10338 sheet S-53, where Wilhoit added Sheffield's steel to the FSS, to create a Support Structure which would, some future day, be able to carry the quite-substantial load of the Intertank Access Arm.

And just for fun, we'll harken back to Apollo Days one more time, and I'll give you a look at 75M05120 sheet 46 with the future IAA Support Structure grafted on to the original LUT, so as you can see how it all fits together in the Greater Scheme of Things.

And in our photograph above these words, we can see what a monster that goddamned IAA is, and yet, when we look at where it would fit in on the original LUT, all of a sudden it gets kind of puny, and you give that one a little thought, and you suddenly realize, "Holy FUCK, that goddamned LUT is gigantic," and... you're absolutely right. That goddamned LUT is gigantic. And it rolls around across the countryside like somebody's little red wagon, and... Jeesus FUCK! What the hell were these people thinking when they first built this shit?

Also, look close, and where the IAA Support Structure makes actual contact with the LUT, I've had to fade the IAA Support Structure overlay a little bit, and that's because it comes in to the actual Primary Framing a little bit behind what they're calling the "Umbilical Arm Support Col." and this will be the best place I'll ever get to draw your attention to the fact that what we've been calling "Strongbacks" for our FSS Swing Arms, was originally an "Umbilical Arm Support Col." on the LUT, and the damn thing runs full height of the whole LUT, and I have a sneaking suspicion that when they designed and built this stuff, they weren't quite sure about exactly where their Swing Arms would wind up being located, and to give themselves the requisite forgiveness, they just ran the damn Strongback full height, and that way, if the Vehicle (the Moon Rocket) changed in some way, or the business of getting stuff into it through the Umbilicals changed in some way, no worries, we'll just move the goddamned Swing Arm up, or down, or thicker, or thinner, or whatever, and our nice tower will permit us to do so.

Which is kind of cool, if you ask me.

Those people were sharp, and that sharpness gets manifested in so very many different ways, most of which you'd never notice, until you really start digging in with this stuff.

And of course, over on the other side of the tower, what they're calling an "Umbilical Arm Locking Col." is what we've been calling the Latchback Strongbacks, and the same deal applies over there, with regards to Full Height Forgiveness.

So... yeah.

Except that...

Is anybody out there... wondering?

Wondering why the location I just gave you for where the future IAA Support Structure would connect with the existing steel of the original LUT... seems to be a little... off?

Seems like it's a pretty good ways down from the top, isn't it?

On the FSS, which we saw in 79K10338 sheet S-53, the top of the Support Structure is only 80 feet below the top of the tower. Only four Tower Levels down.

But on the LUT, which we saw in my doctored-up copy of 75M05120 sheet 46, the top of the same Support Structure which I placed in there is 140 feet below the top of the tower. Which is seven tower levels down.

So what gives?

And herein lies another tale within a tale, and herein we find ourselves stepping back yet again, and this time we're gonna step back all the way to the time when Wilhoit built NASA a nice FSS to put on top of their Launch Pad, so as they could start launching Space Shuttles instead of Saturn V's.

Which was just before I first showed up out there, as Sheffield Steel's brand-new answering machine which they were compelled to install in their field trailer out at the Pad, by Pat Costello, who was the Frank Briscoe Company's Project Manager, because he was sick and tired of not being able to reach Dick Walls, who was Sheffield Steel's Project Manager, and who was also subcontracted to Briscoe, and if they wanted to get paid for the work they did, they might want to play nice with Pat Costello, which of course they did, even though the answering machine cost them a few more dollars per week in overhead costs than they would have liked to spend... but oh well.

And this is reallly late in the game for me to be digging into the details of How The FSS Got Built, but I have not, to this point, told you very much more about it other than the fact that the FSS is a repurposed LUT, and that sounds simple enough, and I've chosen to let it go, up till now, but...

...as a really cool lady I know who conducted the orchestra at Carnegie Hall a few times in her younger days was so fond of saying...

...Ancora una volta da capo al fine!

And there's a little more to it than you might imagine, so...

...here we go. Again.

The FSS is 250 feet tall.

Ok, fine.

And the LUT (just the tower portion of things, not including the Box) is 380 feet tall.

Ok, fine.

But the bottom of the LUT has a funny angled look to it, and the squarely-rectangular portion of the LUT is "only" 320 feet tall.

Ok, ok. Fine, fine.

And you look at the FSS, and you see a nice Hammerhead Crane on top of it, and you look at the LUT, and you see the very same Hammerhead Crane on top of it, and you very reasonably surmise... "Ok, so they cut the top off the goddamned thing, and stuck it down into the concrete of the Pad Deck, and okey dokey, fine and dandy, here you go, NASA, here's your nice new FSS."

Except...

If you were to make that surmise, you'd be WRONG.

Remember children...

...nothing is ever easy out here, right?

Right.

So.

What did they do?

And for that, we'll return to the drawings we've already seen, and I'll toss an extra one in there too, along with a few photographs, and in that way, you will be caused to properly understand How The FSS Came To Be.

We'll go right to the heart of the matter, and start with the smoking gun, which we've already seen, 79K10338 sheet S-53, but this time I've highlighted it differently and maybe take note of how the relationship between the pink and yellow highlighted numbers takes a pretty radical jump up near the tippytop of the tower. And then look at Note 2, down at the very bottom of the drawing.

Son of a bitch, wouldja lookit that!

They excised 60 feet of that LUT, but they did it in a way that would allow them to keep the very top of it, with the Hammerhead Crane and the Elevator Machine Room on the level beneath it included for re-use, while at the same time also keeping the bottom, the strongest part of it, too!

Look close, at the weights of the Primary Framing Columns on S-53 for the Column that runs from FSS Elevation 260'-0" to 280'-0" and then compare it with the weight of the Column sitting directly underneath it, running from FSS Elevation 240'-0" to 260'-0".

The topmost portion of that FSS Column, which runs from 20 feet below the top of the tower at 280'-0" down to 40 feet below the top of the tower at 260'-0", is a W14x61.

And spliced directly underneath it, running the next 20 feet downward, it becomes a W14x193, and below that it quits being a W Shape altogether and changes into a Box Column made out of 1" thick steel plate which has been welded together.

Right there, immediately beneath that Column Splice just above the FSS 260'-0" Elevation floor steel, things all of a sudden get a lot stronger.

And we return to Apollo drawing package 75M05120, and we look at a marked-up copy of Sheet 54, and there you go, there it all is, complete with correctly-matching Column Weights and everything tra la la.

And then, once you know how that shit works on the engineering drawings, you get to look at some of the old photographs, and all that we have left is for Pad A, but they'll do, and you get to see them with New Eyes, and maybe, just maybe, a tiny bit of extra life gets breathed into them, and you gain a little more insight into the mind of Cecil Wilhoit, and dammit, I wish I'd gotten to meet him, but The Fates decreed otherwise.

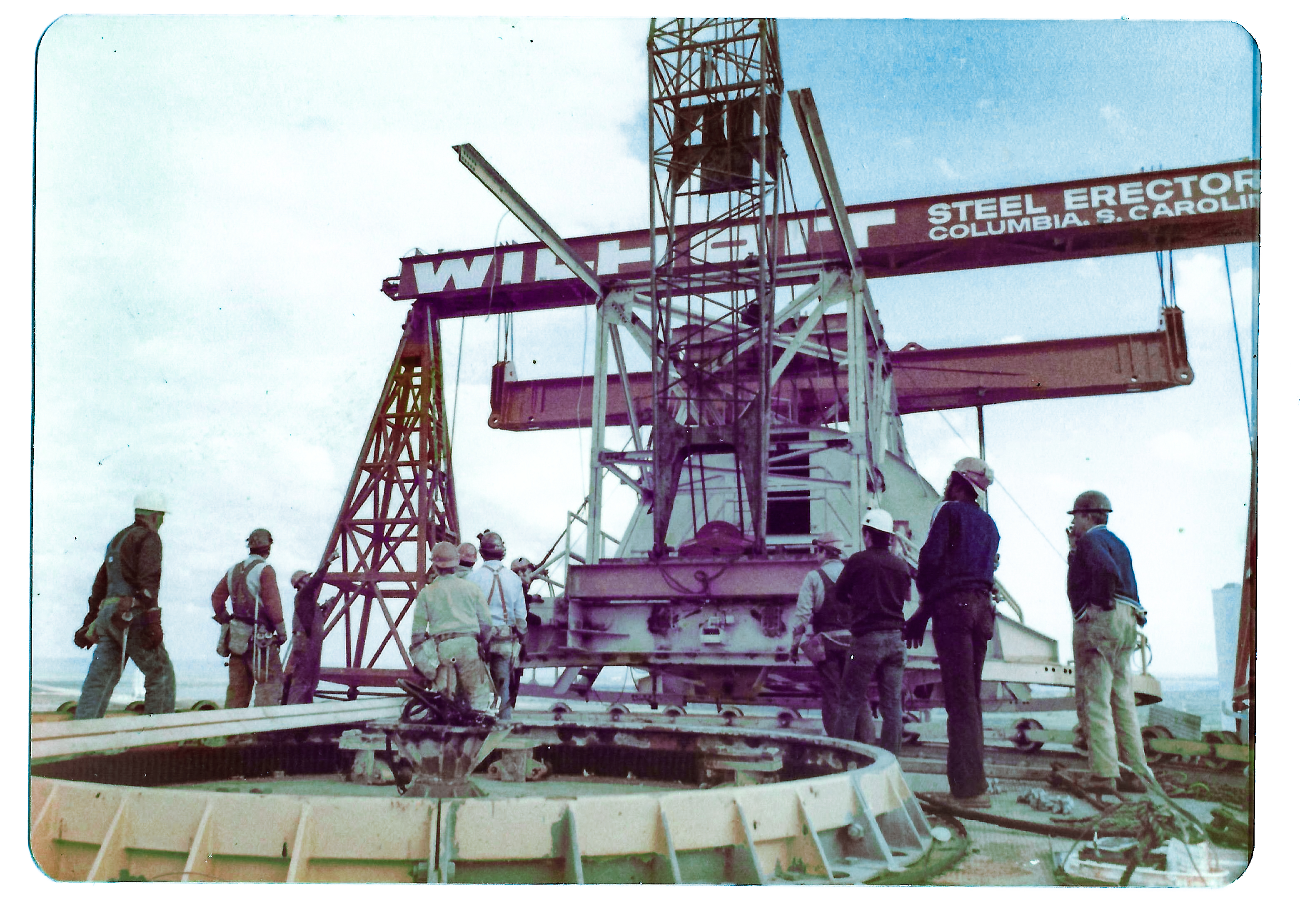

First, the Hammerhead Crane had to be removed.

And don't forget, you're standing on a 40-foot square patch of steel deckplate without handrails, over 400 feet up in the air.

Here's the top coming off of the LUT after they had removed the Hammerhead Crane.

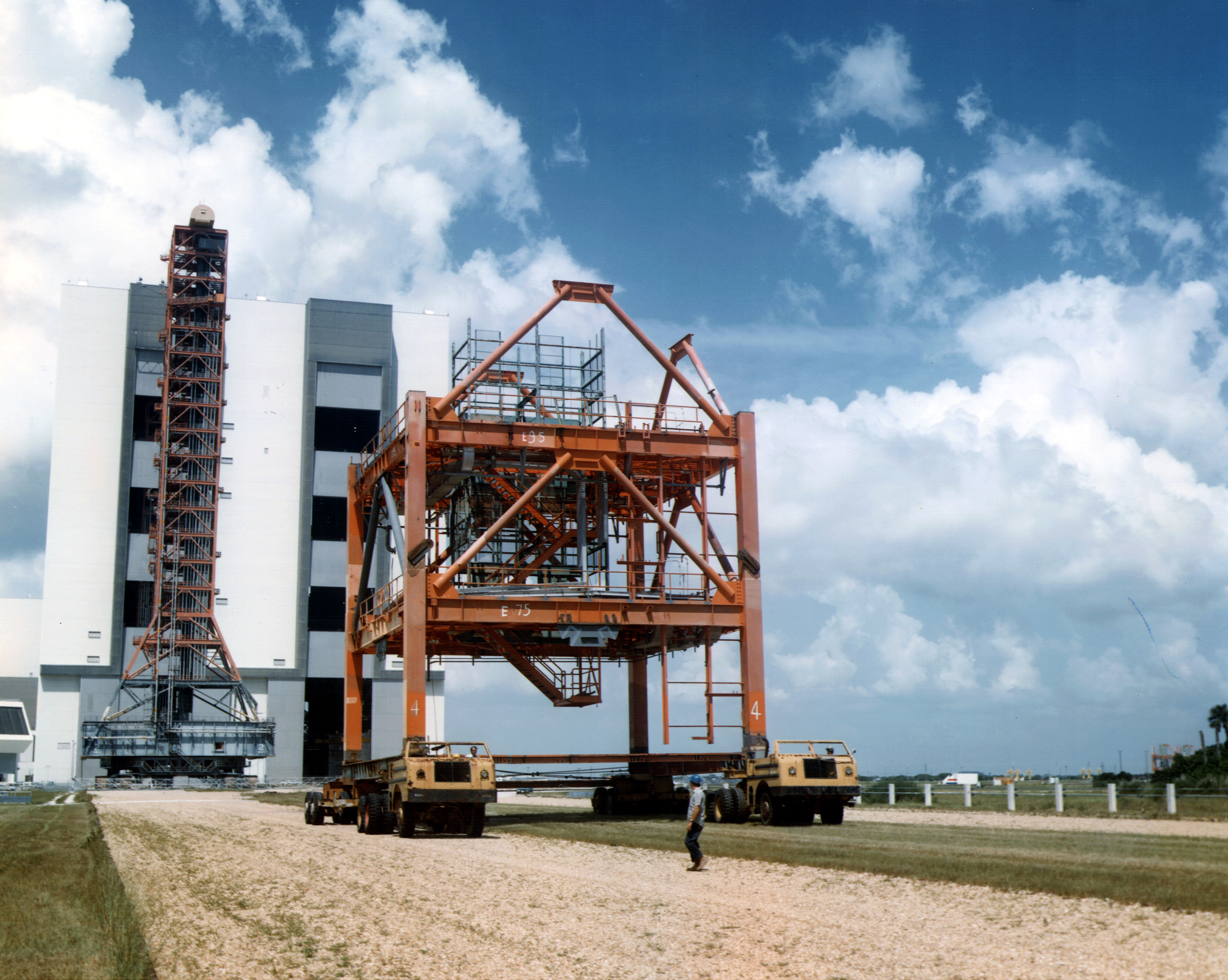

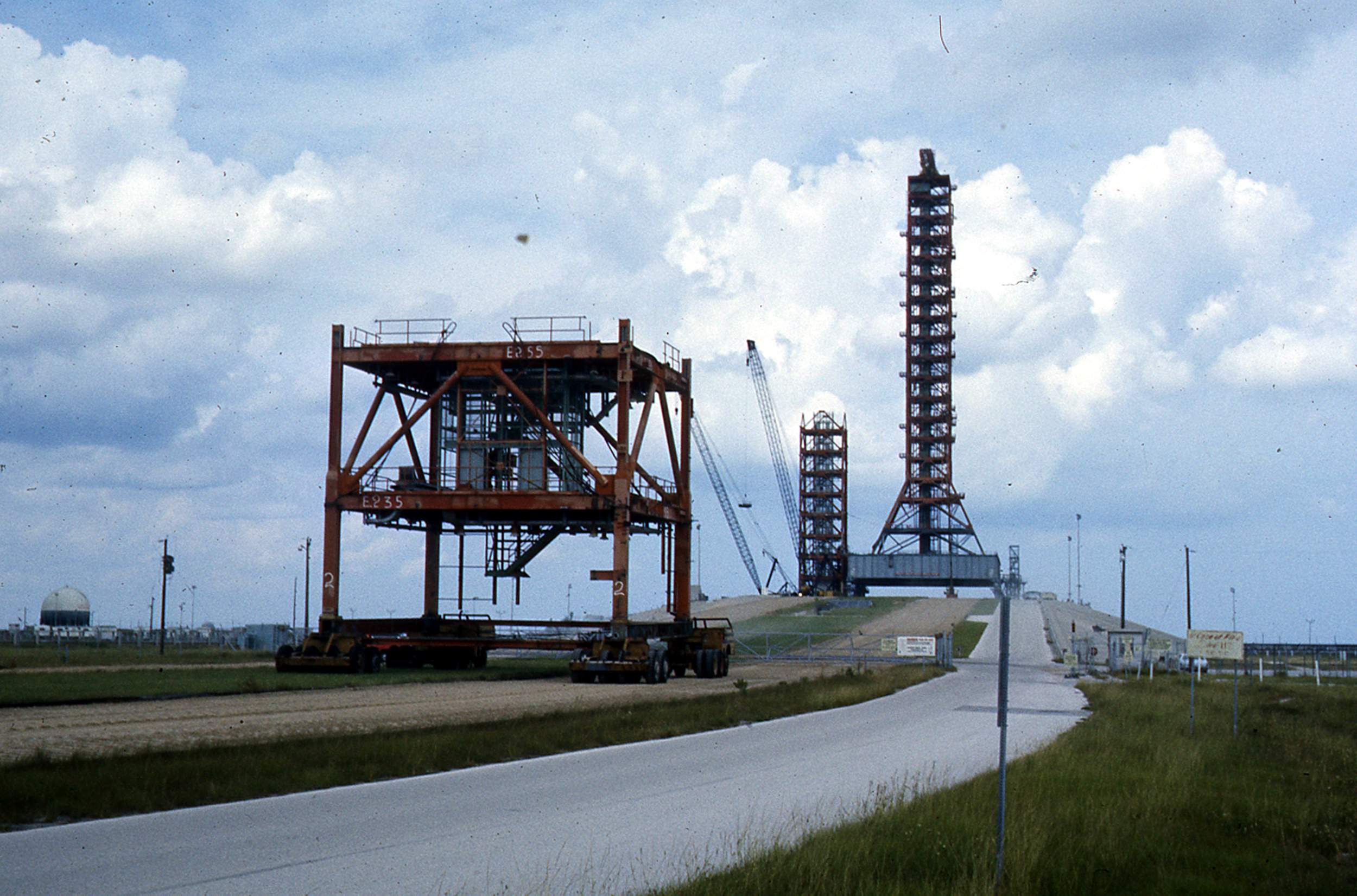

And here's what would become the bottom of the FSS.

And they rolled it down the Crawlerway, out to Pad A. Seven years to the day, after they landed on the Moon for the first time.

And you can tell by simply looking that it was one of those brutally-hot July days when they arrived at the Pad.

By September, they were well on the way.

And they just kept right on going, one 40-foot vertical segment at a time...

Welding them one on top of the other, creating the new FSS as they did so.

Immediately above these words, you're seeing Mobile Launcher 2 (which would be used as temporary falsework for the construction of the RSS) sitting beside it astride the Flame Trench at Pad A. The FSS has now risen over 200 feet above the Pad Deck, and there remains only two more Main Levels to go, one carrying the Elevator Machine Room, and the topmost carrying the Hammerhead Crane.

To the right, across the decking of ML-2, directly in front of its still-intact Launch Umbilical Tower, the Rotating Service Structure would take shape and eventually become self-supporting, at which point it would be retracted across the curved Rail Beam you see spanning the Trench, and ML-2 would be taken off of the Pad by the Crawler, and returned to the Park Site north of the VAB.

In this Pad A image, as all the others showing the erection of the FSS on this page, Wilhoit used a pair of large mobile cranes to erect the segments which made up the growing FSS, but at Pad B, the erection was done with a twin-boom rig very similar to the twin-boom rig you see in the LUT dismantlement images on this page, without benefit of a Mobile Launcher to use as falsework for the RSS, which was instead constructed in its retracted position.

Cecil Wilhoit was extraordinarily savvy, and learned rapidly and deeply as he prosecuted the work, and if he discovered that one of the techniques he was using to do the work might not be fully optimal, he would drop it like a bad habit, turn on a dime, and blaze away at it from there on with a wholly different approach. As I just said, he was extraordinarily savvy.

Return again to Page 35 if you will, for Gene Hajdaj's personal-experience vignette with Cecil, regarding that twin-boom rig which was used to erect the FSS on Pad B.

And I wasn't around for any of it, and I've managed to live a long life, a life so charmed as to still cause me to wonder... why, but if I was forced to choose a regret, well then, perhaps I'd choose the regret of not having been around when this stuff went down.

And all of that just by way of an introduction, to the Support Structure for the IAA!

Who knew?

So now we know exactly where it goes, and how it got there, maybe let's go give that Support Structure a look on the drawings, and once we're fully understanding of it, we can, at last, return to our Lift this day, the one we saw getting underway up at the very top of this page in Image 121.

And when you look at the side of the Support Structure that will be carrying the IAA, face-on, like you see it here on 79K10338 sheet S-96 Elevation At Column Line 6, you start to get a feel for how substantial all this stuff is.

And what's all this "Column Line 6" bullshit, huh?

And we go to a plan view, showing us the IAA Support Structure, and we see that it has its own set of Column Line designations, just like we've already seen with the OMBUU and a few other things along the way, so here's 79K10338 sheet S-93 looking down at the top of it in plan view, to let you see how that works.

And while you're admiring that, maybe take note of how the Lines A and B end of things works, while you're at it.

This is a sterling example of how Column Lines can occasionally go off in funny directions, and just because every Column Line you've ever seen before in your life was square and rectilinear with its surrounding Column Lines, this is no guarantee in the slightest that the next Column Line you cross paths with won't suddenly lurch off at an angle, or maybe some other unexpected weirdness, and if you're not paying attention, yeah, this too can bite you squarely on the ass and wind up costing you real money because you did the Bid Takeoff wrong, and you got the damned job because it was wrong, and you left a pile of money on the table between you and the next-low bidder's bid price, and it turns out there's a whole lot more going on in there that you failed to ascertain, and yeah, now you're low bidder and now you've got to build the fucking thing without going bankrupt in the process.

Our example above is quite benign, and should cause no significant trouble if gotten wrong, but in other places, on other bids...

...look out!

And I mentioned returning to our Lift, once we have full understanding of the Support Structure, and go back to S-96, which I just referred you to a couple of paragraphs ago, and...

...there's a little 20"GH2 Vent Line (NIC) note hiding in there above the 208'-0" level.

What's that all about?

And back we go again, back down the Rabbit Hole again, and this time we're not looking for any white rabbits, and instead we're looking for Gaseous Hydrogen.

Oh joy!

The Intertank Access Arm is also known as the Gaseous Hydrogen Vent Arm, and we already know our Space Shuttle is exceptionally well-endowed with Hydrogen, and of course they fill up the tank with Liquid Hydrogen, and jeezus christamongus, I would suppose that 1,450,000 liters of liquid hydrogen should qualify nicely as well-endowed, and...

"Careful there Lou, this is the same stuff that finished off the Hindenburg, and we don't wanna be letting any of it get loose of us while we're playing around with it out here on this Launch Pad, ok?"

And since we're here...

The Hindenburg held 200,000 cubic meters of gaseous hydrogen, and that's a LOT.

But what happens when we convert that massive 200,000 cubic meters of gaseous hydrogen into liters of liquid hydrogen to let us make a fair comparison with what they're using in the Space Shuttle?

We're gonna take every bit of that hydrogen inside the Hindenburg, chill the holy living fuck out of it, all the way down to a completely ridiculous 423 degrees Fahrenheit below zero, and see how many liters of the liquid which we find inside of the Space Shuttle's External Tank this will wind up rendering us. (Note: This is dangerous. Don't try this at home.)

And the calculation spits back a respectably-hefty 236,600 liters of Liquid Hydrogen, and that's about four standard suburban back-yard swimming pools worth (yes, I know, they're all different, but they all tend to have a pretty standard average size, and I'm going with roughly 60,000 liters), and if your pool is different, well then, fuck you, 'cause I'm still going with 60,000 liters for a goddamned back-yard swimming pool whether you like it or not.

So.

Take a smidgen less than 4 backyard swimming pools worth of liquid hydrogen, let it sit until all of it warms up, boils off, and turns into a gas, leaving the pools empty of all liquid, and then take that, take all that gaseous hydrogen, and pump it into the goddamned Hindenburg, and Hey Presto! up into the air we go, flying high above the city below in perfect comfort, and... well... it's not going to be perfect safety, but they thought it was safe enough... but of course it turned out that they were a little wrong with that part of it, as we all know.

And then you back that Hindenburg's-worth of liquid hydrogen into the goddamned External Tank, and that thing holds just a shade less than a million and a half liters of the stuff...

...and holy shit, that Tank turns out to be worth SIX HINDENBURGS, and if a thing like that was to ever go up in flames...

Ye Fucking Gods!

So ok. So we gotta be real careful with our Liquid Hydrogen when we're out on the Launch Pad, gassing up our Space Shuttle, getting ready to go fly into space, ok?

And the liquid hydrogen is constantly boiling off into gaseous hydrogen, and that hydrogen gas has way more than enough power to blow the whole place clear to hell, so...

We're gonna need to make good and goddamned sure that a thing like that can never be allowed to happen...

And to make good and goddamned sure, they created a whole giant system to deal with it.

And the hydrogen that gasses off from the liquid, inside the External Tank, is, at each and every point along its journey, contained.

And I guess now we're gonna get to talk about that containment System for a little while so as we can understand why this thing (including the piece we're gonna be picking up off the ground and hanging on the side of the tower, if I can ever find a way to shut up about everything else and get back to the fucking subject) got built the way they built it.

It's not like they were looking around for holes in the ground to pour millions of dollars into, ok?

They very definitely had reasons for building this stuff the way they built it.

And we've brushed up against Hydrogen earlier, when we were learning all about the Centaur Porch and all of the platforming that held it up, back on Page 63, but really, all we did was wave at it as we went by, on our way to hang more iron up in the Steel Forest area of the Struts, between the Hinge Column and the FSS.

And that wasn't nearly enough, so now it's time to...

...dig in.

And "The wheels on the bus go round and round, round and round..." No. Wait. Different song. Hang on a minute while I get the right sheet music for this one.

The Hydrogen shows up in Tanker Trucks, and they drive out to the far northeast area of the Pad, far away from everything else, out by the Perimeter Fence, the better to keep their horrifyingly flammable and explosive cargo away from things they don't want to destroy if there's an accident, and...

They pump it, in extraordinarily-cold liquid form, into the Big Dewar.

Where it sits till they need it...

When they pump it through the cross-country vacuum-jacketed lines up to the pad, through the LH2 Tower, which we met way back on Page 41, and from there into the MLP, and from there, through the Tail Service Mast, and into the Space Shuttle's External Tank...

Where it sits till they need it...

At which point they pump it furiously into the SSME's, which burn it with Liquid Oxygen, which we also met back on Page 41, and then the SRB's ignite, and up, up, and away, and off we go into the wild black yonder.

But when it's sitting around in the External Tank, and they're waiting for the countdown to get to T-minus zero, it's constantly boiling off, going from liquid to vapor, and those vapors will keep right on building up inside the Tank, creating higher and higher internal pressures until it POPS, and of course that wouldn't be very much fun, so they vent the vapors away to keep that particular unpleasantness from occurring, via the ET Hydrogen Vent System, and that Vent System contains the explosive gaseous hydrogen vapors, keeping them from blowing the whole place clear to hell somewhere along the line, and it ducts them far away from the sitting Space Shuttle, most of the way back out to the Big Dewar, where they take a little side-trip to the Burn Pond, but they decided the Burn Pond (which was an Apollo Era thing, and which got used for all the Saturn launches) could stand a little improvement, so they ditched it in favor of a Flare Stack (and we'll get to see pictures of us installing that thing, too, later on), which ducted it straight up above the ground, out of everybody's way, where the hydrogen vapors were released into the air and burned, thereby for once and for all rendering them inert, by combining them with oxygen in the air, producing water as a chemical reaction product.

The End.

So let's give it all a bit of a look, shall we?

And now it's time to introduce you to External Tank GH2 Vent Arm, by Garland E. Reichle, and it's only ten pages, five of which are pictures, so it's not like you're going to be reading War And Peace, and you really do need to stop right here and read this thing, all the way through, from the first word until the last, and for the moment, do not trouble yourself over any of the details (or the illustrations) that fail to make proper sense, or even any sense at all.

This one will be the content pass, and we'll return to it for the understanding pass, and of course I'm out there a little ahead of you, and I've gone back through for the third pass, which is the note taking pass, and... this, by the way, is the system which my Intro to College Algebra professor introduced to the whole class, as one of the very first things he said, on the very first day of that course, long long ago, back at what used to be called Brevard Community College, but which is now called Eastern Florida State College, and that's exactly what he said, as he stood up in front of everybody holding the goddamned textbook up in his right hand...

And by this time, I was no longer an answering machine out at the Pad, and Dick Walls, who I have previously said became as a second father to me, forced me at threat of my job, to go to college because my name was starting to show up on paperwork, and certain entities were beginning to question Sheffield Steel about my qualifications for putting my goddamned name on what had by then started becoming very official Space Shuttle Program paper, thirteen long years after somehow escaping Satellite High School with an actual high school diploma, in a smoke-filled haze back in 1969, and in the intervening years, my (already abysmally-poor) math skills had degraded to a point where, when I did as I was ordered to do and went to BCC and signed up, when I took the entrance assessment tests my math "skills" returned as FOURTH GRADE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL level, and I distinctly recall the terror I felt when taking the math test, and coming to the horrified realization that I couldn't even divide and multiply fractions, and... I was really, really, REALLY, starting from the bottom with this one...

...and I'm sitting in a room filled with strangers, and some guy I've never seen before in my entire life is holding a goddamned textbook up in his right hand and going on about...

"If you want to do good in this class, you will read this book three times. The first time is for content, and you just read the words and look at the symbols and illustrations and you don't worry about what they all mean. Simply read them for content, and that way you will know what's actually in the book."

"And then you read it a second time, and this time you're reading it to understand what's in it, so as you can use that understanding of this subject to allow you to solve the problems and learn how algebra works."

"And then, after that, you read it a third time, and on the third reading, you return to those things that you felt like you did not fully understand, and for those things, you bear down on it, and as you grapple with each one of them, breaking them down into small enough pieces that you're able to deal with each piece, one at a time, you make notes in the margins of the book, to tell yourself what each piece really means, and if you do that, following along with me as I teach this class over the course of this semester while you do so, I can guarantee that you will get an 'A' in my class, and that you will understand these fundamentals of mathematics which you will need in order to pass all of the other math courses you will be taking, and, more importantly, you will be able to use mathematics to perform the job or jobs you will be trying to get, and hold, after you have graduated from college."

And from the back of the room came a fairly loud chorus of moans and groans, but for me, sitting front row center (which real estate I was very careful to grab on the first day of class, for every class I took), it was like a light had suddenly been turned on, and I took Jim Williams (cannot believe that name just came back to me as easily as it did) at his word, followed his advice to the letter, note-taking and all, and...

...I will never know what happened to any of the moaners and groaners sitting there behind me, but I imagine not all of it was pleasant, and I, from then on, used this technique in every class, and in several of those classes, the teachers offered extra credit questions on exams, and also graded on a curve, and the hidden nightmare for the moaners and groaners in a system like that is that it's possible, for certain no-fucking-around individuals to bend the curve backwards, and...

...some of those people very quickly learned to hate my guts, and of course all that ever did was to please me mightily, and cause me to redouble my efforts to bend that fucking curve backwards until things started breaking, and...

External Tank GH2 Vent Arm is only ten fucking pages, so read the goddamned thing already!

And for the love of fuck, I've already shown it to you, back on Page 66, but I'm guessing that about three of you actually stopped and read the damn thing for understanding, and now I'm gonna force all of the rest of you to read it for understanding, because if you don't then what follows below will be rendered incomprehensible because of your lack of understanding, and... fuck you, no apologies, no hall pass, no nothing. Do it or don't, the choice is entirely your own.

So read it.

And oh yeah, since you've already seen a couple of the illustrations, in this thing, you're farther along with it than you thought you were, even before you clicked that link and actually started reading for real.

And now that I think about it, the whole IAA, with all of its associated plumbing and mechanisms, has never, to my own limited knowledge and experience anyway, been sensible explicated...

...anywhere.

Sure, there are plenty of sources out there that tell you what it is, and what it does, but none of them seem to get into any of the proper details as regards how the goddamned thing works.

"It vents gaseous hydrogen from the Space Shuttle's External Tank through an umbilical line that disconnects from the Tank at T-minus 0 which falls away from the Shuttle as it lifts off from the Launch Pad."

Well that's just great.

That one, simultaneously, manages to tell you everything, even as it also tells you nothing, and it's always annoyed me, and dammit, I'm gonna see if I can maybe fill in a few of the details regarding how this thing actually works, as a part of the whole system for dealing with the Gaseous Hydrogen that ineluctably comes off of the Space Shuttle, every time they start messing around with fueling the goddamned thing.

Wish me luck, ok?

We'll start in the middle with 79K24048 sheet M-6A, which is the Line Codes Tabulation that includes the GH2 Vent Lines which take the vented Gaseous Hydrogen down from the IAA, toward the Pad Deck, and then across the North Piping Bridge to the LH2 Tower, where it enters the LH2 Trench.

We can see a fragment of it as it takes the turn at the bottom of its run down FSS Side 4, headed out northbound across the ECS Bridge on 79K24048 sheet M-127C. And while we're at it, it would appear as if my surmise back on Page 66 about going to over/under with the pair of Centaur Lines having to be done because of "there's a lot of crap running up Side 4 of the FSS" turns out to be true, because on M-127C you can see the Centaur Lines moving out of the way of that existing GH2 Vent Line, sitting right on the centerline of the FSS on Side 4, and yeah... "a lot of crap" which leads directly to "did not have enough room."

And I went ahead and returned to Image 101, gave it a close look, found the GH2 Vent Line, and marked it up so you can see it. We don't have any good images of this thing, so we're kind of stuck with the crummy ones we've got, and if they ever invent time travel, one of the first things I'm going to do is return to the Pad, back when we were still building it, and instruct 1980's MacLaren to take better pictures goddamnit.

More fragments of it can be seen beneath the Centaur Piping new installation on 79K24048 sheet M-127B, at the corner where it departs the ECS Bridge for the North Piping Bridge above the LOX Tower, and again on the other side of the Flame Trench at the east end of the North Piping Bridge.

From there, the GH2 Vent Line heads out across the same run of pipe supports that carry the Liquid Hydrogen VJ Lines from the Big Dewar to the Pad Body, but it doesn't make it all the way, and out there in the middle of the run, it takes a detour across to the Burn Pond, which I've already mentioned is a holdover from Apollo Days, and which was replaced by the Flare Stack before anybody flew any Shuttles from Pad B.

We'll use 79K24048 sheet M-19, LH2 MPS Key Plan, to see where this ET Gaseous Hydrogen Vent Line stuff goes after it comes off of the Pad Deck, although it's certainly not the correct drawing to be using for what we're doing here. If I had the correct drawing, I'd use it, but, as with so much else in this narrative, I have had to cobble things together using whatever's laying around available to me because NASA Public Affairs categorically refuses to furnish the least mote of Good Information, and has become completely ossified all these years after they were once such a sterling Public Outreach organization, diligently working as hard as they could, to share the wonders of the Space Program with the general public, in a very rewarding effort to stimulate public interest in STEM fields, which in turn rewarded the country as a whole right back, because of all the bright-eyed children and adults who got to see this stuff, and determined that they just might be able to do this stuff, and proceeded with their educations and lives accordingly, and...

...oh well.

But now we're finally getting into some interesting territory, and M-19 is showing us the Burn Pond, but I've marked it to let you know that the Burn Pond was replaced by the Flare Stack, and never got used for any Shuttle flights, but it's a deeply fascinating object, and it pops up all over the place when you start looking around for stuff telling you about Pad A or Pad B, and it was an integral part of the systems that successfully got all of those Saturns up off the ground, and nobody seems to have anything about it... anywhere, and of course that pisses me off, so ok, so I'm gonna take this detour from our detour to take another detour, and...

HYDROGEN. (And if you have any sense at all, you would have known this was coming.)

And Hydrogen is... radical. (Isn't everything out here? Of course it is. That's why we like the place so much. It don't get no more radical than heavy-lift Launch Pads. So let's keep right on digging in.)

And we're out here at the world's largest Liquid Hydrogen storage and transport facility, and...

...Here's the plan: "Don't fuck up."

Simple enough plan, I guess, but with Hydrogen...

Hydrogen really, really, really wants you to fuck up. And it wants to fuck you up, too.

Big time.

Let's get a little background on it, how 'bout?

We'll start out small, with a document that only runs 5 pages, and about half of that page real estate is taken up by pictures, so it's a pretty easy read, and it goes by the ever-so-cheerful name of "EXPLOSIVE LESSONS IN HYDROGEN SAFETY" and it was written by Russel Rhodes, who was pretty much there from the beginning, out on the Cape, and it does a pretty good job of alerting you to the deviousness of systems that are tasked with transporting large quantities of Liquid Hydrogen through plumbing runs that are long enough to keep the stored mass of the stuff far enough away from where it's getting used, to, hopefully, prevent everything from being destroyed should a little oopsie perchance happen somewhere along the line.

So now that you're aware, maybe you're ready for Hydrogen Incident Examples, and it's only 41 pages, so again, not such a long read, and in this one we learn that people are mucking about with Hydrogen all over the place and not just with Big Rockets, and we also learn that Hydrogen apparently has eyes and it's looking for you.

Next, we'll broaden our horizons on the Space Center a little, and include other flavors of cryo, but don't think they gave Hydrogen short shrift in CRYOGENIC TRANSFER SYSTEM MECHANICAL DESIGN HANDBOOK KSC-DM-3557, by Frank S. Howard, Special Projects Branch, DM-MED-1, NASA, KSC, Florida, because it's there, and not only is it there, Frank also gives us our very best look at the actual guts of the Burn Pond, the Bubble Cap Vent Pipes (which are a seriously clever solution to a very knotty and unforgiving problem, and which he introduces to us at the bottom of Page 14) and before we go any further (you have been presumed to have read this thing), we're gonna stop and look at a couple of drawings of the Burn Pond, and maybe when you're done, you'll be able to look at Pad Stuff in the future, and be one of the very few who actually understand the sense of the thing, and why they had to build it and use it, without which.. the whole place may very well have gone up in flames and that would have been the end of that, right? Frank also introduces us to the Vaporizer weirdness that you'll be seeing on the drawings I'm about to show you too, and prior to reading his very well-done document, I had no idea what any of that stuff was for, either. And of course, along the way, he gives us more than enough examples of how things can go wrong, in occasionally spectacular fashion. So... way to go, Frank! Yaaaaaaay!

But before we go look at the promised drawings of the damn thing, we can't just whistle our merry way past REPORT NO. RP-TIVI-0007 to SPACE NUCLEAR PROPULSION OFFICE - CLEVELAND EXTENSION, PHOEBUS-2, HYDROGEN DISPOSAL BURN POND, without stopping to give it the time and attention which it is so manifestly worthy of, and if you ever wanted to learn how Hydrogen Burn Ponds work, well then, this is the document for you. It's got pictures and everything. Runs a little long, to 95 pages, but it's nothing you can't handle, right?

So. Burn Pond.

So. Here's sheet S-202 from the original Apollo Pad B Structural drawings, showing the overall LH2, RP1 (highly refined and purified kerosene), and GH2 Pipe Supports general arrangement layout and dimensions in plan view for this quadrant of the Pad, which I've yellow-highlighted to help you identify the salient features it's showing, and to also let you see the actual dimensions of this stuff, and as you can plainly see, it covers some respectable acreage, and they put that Burn Pond more or less right in the middle of that run of LH2 Piping, midway between the Saturn V and the LH2 Storage Dewar, in an effort to keep the goddamned thing as far from everything else as they could, and of course these are among the numbers that drove the original size and outline of the Pad, as it was first designed and built, so it's kinda nice to have 'em, right?

And then we go to Apollo sheet S-205 to see the Burn Pond itself, and it's pretty brain-dead without the plumbing (which itself is none too complicated, although I'd love to show it to you, but all of this Hydrogen mechanical stuff was handled elsewhere, and I possess none of those original drawings, although I diligently continue to keep looking for them), being just a hundred foot by ninety foot by three feet deep kiddie pool kind of thing (that you could put a lot of kiddies into, all frolicking about in the water under the watchful eyes of... maybe even Wernher von Braun himself, who knows?), but despite it's bare-bones simplicity, it would have been a wonder to behold, to actually watch this bitch in action (making double-damn good and sure that every last one of those kiddies had been properly and fully accounted for and gotten the hell out of it and far far away from it, first) with the water in a state of agitation as the three hundred degrees below zero Fahrenheit hydrogen gas was coming out of all the Bubble Cap Vent Pipes from just beneath its surface, and turning into an invisible full-coverage blanketing inferno of 4,000 degrees above zero Fahrenheit see-through-clear hydrogen flames all across the full area of the Pond. I can only imagine the uncanny and not-quite-right sound it made, and pity the poor birds and bugs that did not recognize or understand what the heat-wavy look of more distant objects seen through those clear flames really meant, blithely flying into the unseeable edge of that wall of flame, and... alas, I wasn't invited to that party, so I cannot tell you how fucking cool that thing was, when they were running it. But I'm pretty sure it was really cool.

But I would also be extraordinarily leery about ever approaching the sonofabitch because... wouldn't it be a shame if something untoward was to occur while in the near vicinity of it, and yeah, they're pretty well organized out here, and the odds of a thing like that actually happening are vanishingly low, but to be there at the edge of this motherfucker idly splishing your hand in the water while bemusedly considering how to smuggle a few goldfish into the thing just for laughs, and all of a sudden... fffsssSSSHHHOOORRRRFFFFFFFF!!!

And a thing like that could go from pleasant to unpleasant pretty damn quick, and...

Of course they were all made to read SAFETY STANDARD FOR HYDROGEN AND HYDROGEN SYSTEMS... but still...

I'd still be mighty mighty mighty leery of ever getting any kind of close to that thing, anyway.

And since we're already in the area, sort of, farting around with all this stuff, here's 79K24048 sheet M-20 to let you see what that big LH2 Dewar is sitting more or less directly above, including the weirdly-outsize Vaporizers (there's two of 'em, and that redundancy with this thing should be telling you just how critical it was to the operation of the system when it came to actually moving the Liquid Hydrogen from the Dewar to the Pad), and you are presumed to have already read it, but here's a link to Page 8 of CRYOGENIC TRANSFER SYSTEM MECHANICAL DESIGN HANDBOOK KSC-DM-3557, where Frank tells us what the deal is with the Vaporizer, for all you slacker fucktards who failed to read this document earlier, despite having been told to do so, for good and sufficient reasons.

Ok.

That should be enough of that.

And now we know what the back end of this stuff looks and acts like, maybe we can return to the front end, and figure out what the fuck is going on with all that ridiculously-contrapted rigamaroo with the Intertank Access Arm, which, in case you have forgotten, is the whole point of this particular page of the narrative, it having been kicked off with the first in a series of photographs of Ivey Steel's Union Ironworkers hanging that monstrosity on the Fixed Service Structure at Pad B.

We departed the scene of that particular crime while still considering the Support Structure on the north side of the FSS, that holds up the IAA, just after discovering some sort of 20" GH2 Vent Line (NIC) on 79K10338 sheet S-96, which took us all the way back to Wilhoit Days on the Pad, before I showed up as Sheffield's brand new answering machine.

And then we jumped away, working in reverse, from the middle, to the back end, winding up all the way out to the Big LH2 Dewar, far from the scene of our original crime, in what turned out to be a very necessary effort to gain enough proper understanding of the extraordinarily-violent potentialities and extraordinarily-devious complexities inherent with using Liquid Hydrogen as fuel, to let us then move forward with further understanding of exactly why and how they vent the stuff in gaseous form away from our Launch Vehicle... safely.

But now we're gonna need to turn back around and start working from the middle to the front end, where the GH2 Umbilical Carrier Plate is in direct contact with the External Tank, and in so doing, lean in to things a little harder, and get for once and for all to the bottom of the matter, as it relates to keeping the Shuttle from blowing itself up while still sitting on the Pad, mid-twang, ramping the SSME's up to full power, prior to SRB Ignition and Liftoff.

You now know exactly what it is, so here's our GH2 Vent Line running across both the IAA and its Support Structure, headed toward its final destiny with a Carrier Plate that's flush up against the External Tank, and you see it shown in plan view on 79K24048 sheet M-343, and this was originally a worksheet, which I needed to create in order to work my way through the Hall of Mirrors that is 79K24048, keeping in mind that many of those mirrors in that hall are cracked, and missing pieces, or completely not there at all, or, most alarmingly, are distorting funhouse mirrors, and... we certainly do wish we had the correct set of drawings for all of this thing, but...

...we do not...

...and I decided to just go ahead and use the damn thing right here in this narrative, and I'm just gonna dump the damn thing on you without any up-front explanation of it...

...and then I'll attempt to walk you through it as best I can later on as we continue on our Journey of Wonder, Through The Land of Hydrogen...

...but this fucking thing is COMPLICATED...

Which is probably why nobody else has ever taken a run at properly explaining it to anybody beyond their own narrowly-defined home world of technicians, engineers, and program managers.

And I flagged a couple of small G (can't be Liquid, because they have no proper insulation or vacuum jacketing) H2 lines, pressurized to 3,000 psi, on M-343, and you're like... what's the issue here? And you lose sight of where you really are, and just how horrifyingly dangerous the place is and...

Ok, it's wet dress-rehearsal day, and we need to fill the Tank to proof the system, but we're not gonna actually burn all that Liquid Hydrogen fuel we filled that goddamned tank up with, and instead we're gonna drain the Tank...

So ok, so drain the fucked-up Tank and be done with it, and shut up about it already.

But wait...

What's going to fill the gigantic void now occupying the Tank?

We gotta fill it up with something, or it might collapse, or perhaps just bend a little somewhere, or maybe place an unacceptable strain on something that was never designed to see any such strain (everything has been pared down to the bone, in a crazed effort to keep the whole shebang light enough to even reach orbit in the first place), or maybe it'll just want to get all pissy about giving us our Hydrogen back, and try to hold on to it via vacuum suction, and that leads to its own set of troubles which we very very much want nothing to do with...

And we can't just turn the valves and let what's in the Vent Line back into the Tank, 'cause that stuff was a severe fire and explosion hazard for every second of its existence, and you never let a Hydrogen Vent Line suck any air back in when the pressure drops, and those valves are closed, and they're going to stay closed..

So air getting together in any way shape or form with Gaseous Hydrogen, no matter where it came from, is strictly forbidden, so... ok, how 'bout we use some of the Nitrogen we've got all over the place that we use (among other things) as a non-flammable purge gas?

Nope.

Hard no, on that one, too.

Nitrogen will liquefy at minus 321 Fahrenheit, which is almost exactly one hundred degrees warmer than the Liquid Hydrogen we're fucking around with here, and if the stuff that we're trying to use to fill a void left by the departure of our Liquid Hydrogen decides to liquefy, itself, well... there goes your gas pressure, and we're right back where we started, and that's not good, and bring it down another 25 degrees Fahrenheit, and the goddamned stuff freezes solid, and the thought of blocks of frozen Nitrogen getting into the innermost nooks and crannies of our Hydrogen System, while we're moving Hydrogen around in it, is a deeply frightening one, and perchance you used it anyway, maybe even on Launch Day... well... it would freeze on contact with the surface of the Liquid Hydrogen in the Tank, and that frozen Nitrogen would promptly sink to the bottom, down to where the inlets for hungry turbopumps are looking for a drink, and start accumulating, and those turbopumps will drink Nitrogen rocks just as quick as they'll drink a refreshing beverage of Liquid Hydrogen, and presuming the Nitrogen rocks did not simply plug up the inlet and block the flow of liquid, causing the turbopumps to cavitate (yet another surefire way to blow the whole place sky high), when the Nitrogen rocks (or even just small pieces of Nitrogen gravel, or even Nitrogen sand) pass through the inlet into the plumbing and eventually make it to the ferociously-high-speed spinning turbine blades in there, the blades and the bearings might not like that all so very much... and... NO.

Hard no on Nitrogen.

We can use Helium, and in certain circumstances they do, but Helium too, comes with its own set of technical and financial problems, and it turns out, in a lot of cases, you wind up needing...

Gaseous Hydrogen to keep things both ventish and supplyish from sucking air and blowing the whole place to hell, and of course when you're doing that you're gonna need to be... venting your GH2 Purge Gas, and that ties you right back to your system for getting the damn stuff well and truly the hell out of here, in a fully contained way, all the way back to your Burn Pond or Flair Stack, and once you start actually building this stuff...

Plumber's Nightmare does not even begin to describe what you wind up with, trying to keep from sending the whole place up like a Russian oil refinery that the Ukrainians decided they didn't like having around anymore.

And we recently learned in CRYOGENIC TRANSFER SYSTEM MECHANICAL DESIGN HANDBOOK KSC-DM-3557 how they use pressure (which is why the Vaporizers) instead of pumps to push the Hydrogen around in the system, and that little nugget of information might go a long way toward explaining the little "HYDR RETURN (3000 PSI)" and "HYDR SUPPLY (3000 PSI)" notes flagging a couple of quite small (¾" and ½") lines, in the upper left-hand area of M-343, because otherwise... whuffo three thousand pounds of pressure per square inch in a system that's only supposed to be venting some excess Gaseous Hydrogen out of our External Tank whenever we're fucking around with fueling operations out here on the Pad?

And I am most manifestly not qualified to talk about any of these (and no end of other) complexities and considerations, so you get to look at some of these drawings, and...

Fuck all if I know what that shit's there for, or what it's doing, or why they were (without the slightest doubt) forced into doing it that way.

Can't help ya.

Maybe try the next office down the hall.

Good luck and godspeed.

So now we return to 79K24048 sheet M-343, and this time we're looking at the existing FSS and IAA Support Structure in pink, and the part of the IAA that we're lifting today in blue, and you can flip back up-page to Image 121 if you'd like to compare it with what this plan view is showing, and you can verify for yourself that the Swing Arm part of things is very definitely not part of the IAA structure that we lifted, and that damn Swing Arm turns out to be just about a confusing motherfucker when it comes to understanding this thing, so...

Oh boy, here we go, Swing Arm City.

And when it comes to imagery of Space Shuttles lifting off, this whole side of things is quite-poorly represented in what you generally see, and that's because it's kind of stuffed in there between the tower and the bird, and for the most part, everything you get visually is looking from the other direction, from somewhere east or south of things.

And "East" makes perfect sense, because the FSS and the RSS are not blocking the view, but "South" is a little less obvious, and you get that end of things because that's the side of the Stack that the Orbiter is on, and everybody wants to see the Orbiter, and nobody wants to see the stupid External Tank blocking it from view, and...

For the most part, our present area of interest is poorly-represented, and you never get to see what's going over there on the northwest side of the Stack with the IAA at Liftoff.

But there is stuff out there (NASA, if nothing else, is pretty damn good at getting lots of videos of their Spaceship taking off from every imaginable angle), and the reason nobody ever sees any of it is because the fucked-up Media invariably chooses those views that best show the Orbiter as it's coming up off the Pad, and of course the IAA is nowhere to be seen from those Media-favored viewing angles.

Yet another reason to globally fear and mistrust the goddamned Media, all of it, everybody's, even mine, as a blanket policy ab initio. Media bias comes in a million different guises, pollutes and distorts our thinking in a million different ways, and a lot of it consists in blind spots that are created because the goddamned Media demands the absolute maximum Wow Factor, and an awful lot of the world around us simply fails to show up because of this, and some of it's pretty fucking important, but people think they know what's going on anyway, because blind spots... are pretty fucking hard to see, eh?

And I've grabbed a pretty good vid from NASA that shows what we're looking for, and we're gonna see it here soon enough, but first, a little more background on the stupid Swing Arm, ok?

And for that, best we'd start out by asking ourselves, "What's that fucking Swing Arm even for, anyway?"

And the answer to that turns out to be one of those things that lives in one of those blind spots I was just warning you about, and...

So ok, what is it?

And what it is, is the means by which we can attach the actual Vent Line to the side of the External Tank, so as we don't immolate ourselves in an Oxyhydrogen Inferno, and the actual Vent Line, the actual thing that attaches to the Tank, is a laughably-minor-looking piece of the overall IAA System.

Complicating the issue, our previously-referenced Media-induced dearth of information prevents most people from even having an awareness that the Swing Arm and the Vent Line are actually two very separate and distinct things, completely independent of each other, moving in completely different ways and directions, at completely separate times, in response to completely separate needs and events.

Onward.

They knew they were gonna have to deal with this bullshit, the instant they settled on a design for their Space Shuttle that involved the use of Hydrogen for Fuel...

But in the very beginning, in earliest Shuttle Ur-time, back at the very top of the Design Cascade I told you about waaaay back on Page 6...

...nobody knew nuthin.

Size? Shape? Weight? Payload? Booster? Cost? Look? Smell? Feel?

Who the fuck knows?

Was it gonna be small enough to just sit it down on top of a existing military rocket that had already been designed, built, tested, and proven? Maybe. Maybe not.

Was it gonna be fucking GIANT and lift off of the pad carried by some damned Winged Monster or other that would return to the Launch Site on its own, making the entire system totally and completely reusable? Maybe. Maybe not.

Was it gonna be straight-wing or delta-wing? Nobody knew.

Was it gonna be the most stupidest-looking thing you've ever seen in your life? Let's hope not.

Was it gonna look like a cross between an XB-70 and a stuffed turkey? Well... that might be better than Chrysler's idea.

Was it gonna reuse very-slightly-modified Apollo flight hardware? Maybe. Maybe not.

Was it going to use very-slightly-modified Apollo ground hardware? Maybe. Maybe not.

Was there simply no end of daffy design concepts and proposals floating all around out there like deranged snowflakes in a brain-damaged blizzard? You bet your ass there was!

And at the close of this Paleoarchean era, time, money, and political expediency had forced them into the corner they wound up in, complete with the use of Hydrogen as fuel, and a, sort of, sense for what the Pad GSE (Ground Support Equipment) was gonna look like, but even then, when it came to venting the goddamned Hydrogen away from this stuff, there were still... many questions.

And what about the Pad? What the hell are we gonna do about that?

And I told you to read it, farther up on this page, and yet here I am, holding you by the goddamned hand, showing you image by image, some of the possibilities that might have eventuated with what became the IAA, as the slush ice of the design was still congealing into the solid block which wound up going into production.

And they got it reduced down to three "finalists", and as engineers are wont to do, they very creatively named them "Concept 1", "Concept 2", and "Concept 3."

And Concept 1 got rejected first, because it introduced a weight penalty in the form of additional plumbing that they could not bear, because it ate far too deeply into their performance numbers, taking away too much Payload capacity (which, of course, in a "real" world, is the whole point of the operation, but the Space Shuttle, from the very outset, dwelt in a world that was only part real, and the other part was political, but either way, the additional plumbing required for Concept 1 wound up being too heavy, so... nope).

Concept 2 got the axe next, after they realized that it would involve a lot of time and expense, modifying the MLP, in addition to the most very unpleasant fact that the Shuttle just might HIT the damn thing, coming up off the MLP, and of course that would be kinda bad too, right?

Which left them stuck with Concept 3, which was very sub-optimal, but they had to use it, and it was not a Happy Thing, but it's what they wound up with, anyway, and as with every other goddamned drawing of this thing that I've ever found, our drawing is near-useless for understanding (what is, admittedly, a subtly-complicated thing, none too easy to explain in a single image), so I've marked up the Concept 3 drawing to, hopefully, let you see what's going on with it.

And now at last I get to introduce you to The Elephant's Trunk, which is the innermost heart and guts of the whole system.

And out on the Pad, everybody, and I do mean everybody, always referred to that final portion of the GH2 Vent Line which consisted of both flexible and hard line-segments, and which simply fell away from the Shuttle at the moment of Liftoff...

...as The Elephant's Trunk.

Ev-re-body.

All-ways.

Elephant's Trunk.

So get used to it, 'cause that's what it is.

And here it is, in action, in the video I promised you I'd show you, a little while ago. That's it, a little left and below center. Thinnish white (which is a solid coating of ice, which is telling us that the GH2 it's carrying away from the Tank is fucking COLD) line looking thing at about a forty-five degree angle to the External Tank, which it's attached to on the left side. And around 19 seconds in, when we start getting some real action, but before Liftoff, it begins to shiver violently (you can't see it in the vid, but it's definitely happening), shedding its coating of ice, which falls away as a cloud of large and small pieces of debris. And just about 26 seconds into this video (which is really excellent), following the whole Stack bending left an alarming amount for a gigantic thing that everybody expects to be as rigid as building, but it's not, and then bending back, the whole line just... drops. Drops straight down. As the Shuttle starts moving straight up and also moving toward it, and you better believe that goddamned thing has got to be out of the way in time, or otherwise... bad juju. Very bad juju, just as soon as the Space Shuttle starts rising.

And when I just told you this whole system was sub-optimal, perhaps now you can start to get a better idea of why I might say a thing like that.

It worked. Let the record show that it worked. Every single time. It never hurt anybody.

And here's another video, that focuses primarily on the Carrier Plate, but is also simple enough and generally-informative enough that I figure it might be worth including, in an effort to increase your understanding of the overall system.

But every single time the Space Shuttle lifted off, you can assure yourself that there were certain people, in certain places, whose hearts were in their throats, until the goddamned thing got far enough up into the air to leave this motherfucker behind.

Every. Single. Launch.

No exceptions.

The Elephant's Trunk was one of the very most frightening elements in the whole place.

And you look at it with Eyes That Do Not See, and you think nothing of it. And really, you think not at all.

But other eyes were having other thoughts every single time.

And for some reason, in every operational drawing of this thing, you always get the Swing Arm part of it in its extended position, with the Elephant's Trunk showing up as some sort of ill-defined integral part of the swing arm.

But the Elephant's Trunk was no such thing.

And you just never get to see it sitting out there in it's work position without that goddamned Swing Arm in there, mucking it all up, and blocking proper understanding of this stuff.

And when it's done wrong, like it's done here on 79K24048 sheet M-338, it's near-impossible to understand.

But if some kind soul comes along and fixes the goddamned thing, giving you a second view with that miserable Arm properly retracted, and out of the way, then all of a sudden that altered 79K24048 sheet M-338 with the Swing Arm retracted suddenly starts to make one hell of a lot more sense, and...

...you're welcome.

And it turns out we can actually see this thing, sort of, not really all too well, but... well enough, on our photograph at the top of the page, Image 121.

Although our old friend, Structural Steel, doesn't really want us to.

So I had to work that image a little bit, to let you see the item in question, and to give you a bit of information as to what it is that's visible there as part of the IAA we're lifting.

And here's a copy of Image 121, with the GH2 Hydrogen Vent lines all nice and labeled up for you.

And now we're starting to learn how this thing actually works, and, although it does not look like it, it works an awful lot like any of the other T-Zero umbilicals you've already crossed paths with in no end of included links to reference documents, and at least one vid, in this thing, and what happens is that they snatch it a short distance away from contact with the Vehicle, which allows them to then immediately swing it a farther distance away without catastrophically grinding, gouging, or tearing it across the side of a Launch Vehicle which may be drifting in their direction as it sways and shudders and shimmies and shakes upward into the sky while they're doing so, and the only real difference with this thing, as opposed to the Swing Arms for a Saturn V, is that instead of getting swung across to the side, Arm and all, this thing is simply allowed to fall and the "Arm" part of things never enters into that part of the equation.

So it's the same, but it's different, too.

Explosive bolts on the Umbilical Carrier Plate at the far end of the Vent Line blow, detaching it from the External Tank, and the Vent Line along with the Carrier Plate that's still firmly attached to it, immediately gets jerked two feet straight back and away from the now-moving Shuttle by the pivoting Pivot Arm which has been under some pretty good tension the whole time because of a dropweight with a line reeved over a pulley, applying sidewise pulling force on it from inside the IAA.

If the explosive bolts fail to blow (never happened, but they for sure as hell weren't taking any chances with this thing), the Shuttle would rise up far enough that the Secondary Release System would kick into gear, and snatch the Carrier Plate off of the External Tank via the use of a Lanyard that was connected to the Carrier Plate on one end, and the lower front end of the IAA on its other end. And if the bolts didn't blow, the Shuttle would keep rising, and the Lanyard would suddenly came taut, and the moving end of the Lanyard would stop cold, then and there, like all good wire ropes do when you've pulled them until there's no more slack to take up.

This of course keeps the Carrier Plate from being pulled any farther upward by the Space Shuttle it was still attached to, and more or less rips it off the side of the Tank, which of course kept right on going up into the sky following Liftoff.

And yes, the system was designed with this in mind, and the valves would snap shut either way, and it's not like there'd be some kind of hole opened up in the side of the External Tank if this thing was ever invoked, and yes, just as soon as the Carrier Plate gets torn off the side of the Tank and becomes disconnected from it, the Pivot Arm immediately does its thing because of the falling dropweight, snatching it two feet sideways away from the tank, just as soon as the disconnection occurs.

So the Pivot Arm snatches the Vent Line sideways no matter what happens. Immediately. Once that Carrier Plate releases its hold on the Tank and the dropweight suddenly becomes free to fall.

And it's that "Pivot Arm" linkage kind of deal, up there in the top corner of the Blast Shield, the thing that wants to initially pull the Vent Line 2 feet straight back away from the Tank at the instant the explosive bolts fire, that seems to be the source of everybody's confusion, or utter ignorance.

And the Pivot Arm works exactly like any other linkage arm you've ever encountered in your life (and linkage arms are as common as dirt, and can be found everywhere). It's hinged up on its top end, and it has a lanyard of its own hooked to it, internal to the IAA, using the dropweight I mentioned, to yank the lower end of it back away from the Tank along with the Vent Line which is firmly attached to it, down at the bottom end of the Arm. The bottom end of the Pivot Arm doesn't get yanked very far, (it's only two feet, right?) but it's far enough, and as that happens, the Vent Line which is now completely disconnected from the Tank, suspended solely by its hinged connection to the bottom of the Pivot Arm... falls down. Straight down, swinging on its hinge which is attached to the retracted lower end of the Pivot Arm, down and away from the rising Space Shuttle as it does so.

And when you think about it, that's actually pretty cool, and it gets the work done with a lot less hardware to do it, and up up and away we go, unencumbered by any (still-attached, torn-from-the-tower and dangling, and already maneuvering to kill us all in the next few seconds) GH2 Vent Line apparatus as we do so.

So it's weird-looking, and it's a little hard to understand, but it's actually a pretty slick system they cooked up for this stuff.

But certain people, in certain places, worried deeply about it anyway, every single time.

And it turns out that despite the simplicity of the concept, letting the Vent Line simply fall, there turns out to be a lot of complicating factors, and some of them are pretty non-obvious.

It's not the kind of thing that jumps out at you and causes you to consider it, when you're considering the whole business of a falling Vent Line, but the damn thing has got to go somewhere, and that somewhere needs to accommodate the damn thing in some way, instead of just being some kind of empty space where it can dangle freely, after falling. It needs a Latchback, and we learned all about Latchbacks with the GOX Arm, but of course this one is going to be significantly different, and they're not even calling it a "Latchback" anymore and instead it has become an "Umbilical Retention Mechanism" and sometimes they call it the "Deceleration Unit" and of course, when you're actually reading the documents you discover that sometimes they use Metric, and sometimes they use US Customary Units, and isn't that just too much fun?

And on top of that, when they revisited this stuff (which they're always doing, looking for oversights and hidden flaws in their original lines of reasoning and understanding of the systems they're implementing, in a never-ending effort to keep from... falling afoul of Bad Things), they discovered that there were certain scenarios in which... Bad Things could happen in the few seconds it took for the Vent Line to fall. This thing is scary, and everybody on the inside knew it was scary, and none of them were inclined to turn their backs on it, in any way.

And they found issues with the Secondary Release System Lanyard, which is the wire rope attached to the Vent Line Assembly, out at the Umbilical Carrier Plate, which was there for just in case, and which it turned it out was never invoked, not even once, but that didn't keep them from wanting to make damn good and sure that... just in case... this thing couldn't decide to unexpectedly turn on them.

So ok, here we go again with this stuff. Sigh.

And In The Beginning, they originally decided that it would be enough to let the far end of the Vent Line where the Structural Support for the Forward Flex line is located, fall into the Deceleration Unit, which is a surprisingly-contrapted thing that lives on the front of the IAA, down at the bottom, and let the Lanyard just sort of flop down with it, and wind up wherever it wound up.

And events conspired to cause them to revisit this stuff about how the Lanyard works, as regards what happens immediately after Liftoff, and as regards what happens after the Vent Line has fallen all the way down into the Deceleration Unit where the Structural Support for the Forward Flex Line enters the Decel Unit and bangs into that wire in there. Here's a closer look at that Structural Support for the Forward Flex Line (it's too small, but it's all we've got) in this marked-up copy of 79K24048 sheet M-345, labeled in green, along with all of the other main players that can be found out at the terminal end of the GH2 Vent Line where it meets the External Tank.

So they came up with a couple of modifications, and you can read all about it here in Modification and Development of the External Tank Hydrogen Vent Umbilical System for the Space Shuttle, by our old friend Bemis C. Tatem Jr., whose work we've seen before, twice even, once with the PGHM back on Page 36, and then again more recently with some of the Centaur Rolling Beam stuff on page 63. So I guess Bemis is a pretty well qualified person to be using as a source for this stuff, too.

And then, after that, more problems cropped up, and with the launch of STS-108, the goddamned Vent Line failed to even enter the Decel Unit, and instead, it smashed violently into the IAA Structure surrounding it, and pieces flew, and had some of those pieces flown into the rising Orbiter, or External Tank... that could have ended things, then and there, and...

The Decel Unit was modified, along with other recommended actions, and despite the deeply-frightening reason for the creation of this document, Gaseous Hydrogen (GH2) Vent Arm Behavior Prediction Model Review Technical Assessment Report (which is the source document for our drawing of the Decel Unit) is an excellent piece of work because it contains graphics that let us see the mechanical workings of this stuff in a clear and understandable manner, and I recommend you give it a look, 'cause there's some pretty cool stuff in there.

Nobody ever actually liked anything about this whole IAA ET Gaseous Hydrogen Vent thing, and I never heard so much as a single kind word about it the whole time I was having to deal with it out on the Pad, and in addition to everything else, some people worried that the Orbiter's Left Wing might HIT the goddamned thing on its way up off the MLP, and everybody feared and mistrusted it deeply, and... those who knew had way more than enough good reasons for their fear and mistrust, and...

And that has got to be just about enough of that shit, and you are now presumed to understand this thing, and can we please get back to the fucking IAA Lift? Pretty Please? With cream and sugar on top?

And here we are, and we're on our way up.

With a hundred thousand pounds of steel.